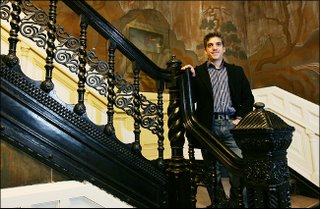

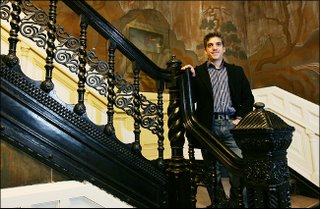

Joe's fondness for historic buildings attracted him to a 500-square-foot co-op in a landmark 19th-century building.

March 12, 2006

What Explains the 'Aha' Moment

By STEPHANIE ROSENBLOOM

BETH LOWY protested all the way to the front door. Unlike the previous apartments she and her husband had owned, the co-op apartment in a town house on West 78th Street had no doorman. That was a deal breaker. But as is often the case with love, preconceived notions tend to go out the window.

"I don't want to live in a place with no doorman," Ms. Lowy said as she and her husband, Tom, first approached the building. Once they entered the apartment, however, she changed her mind "in a nanosecond."

From the backyard garden to the coffered oak ceiling in the master bedroom, Ms. Lowy was smitten. The Lowys bought the apartment in 2004 and Ms. Lowy said it is as beloved to her now as her former apartment in the El Dorado on Central Park West, which she and Tom sold to the Irish rock star Bono in 1999. She occasionally misses having a doorman, particularly when she is unloading the car from Costco. Yet for the first time in nearly three decades in New York, Ms. Lowy, who grew up in Dallas, said she feels as if she is living in a home.

Still, she cannot pinpoint what melted her heart. The apartment, she said, "just feels right." Countless home owners know the feeling. And like Ms. Lowy, many say it is difficult to explain why they knew they had found "the one." Some attribute it to the way sunlight seeped in. Others say they were won over by details like a marble mantelpiece or basket weave floor. Yet whether or not they are able to articulate their feelings, they all have notions of what home is — and most recognize it when they see it.

Through the years, the meaning of home has evolved far beyond a Three Little Pigs notion of shelter. It is a respite, a refuge, a conveyor of style or status, a gathering place and a lockbox of memories. Yet what triggers our affections for a space may have more to do with the experiences we had in our childhood homes than with the space's size or amenities.

"We all have an environmental autobiography, our own past history of place, and we rework that past history of place often unconsciously," said Toby Israel, the author of "Some Place Like Home: Using Design Psychology to Create Ideal Places." "While we may think we're purchasing a home based on rational criteria, like nearness to work or number of bedrooms, often what drives this choice is this past history of place."

Psychologists who study interactions between people and environments say that buyers often unknowingly seek out spaces that are physically evocative of childhood havens. And the aha! feeling that a person experiences upon walking into a space can often be attributed to his or her recognition of unconscious yet happy memories. On the other hand, those who gravitate to a housing location or style that is the opposite of what they had in childhood are frequently making a statement that they are not like their parents.

"Many of us tend to repeat in our housing choice — in terms of design or location or how we furnish it — something from our childhood home," said Clare Cooper Marcus, the author of "House as a Mirror of Self: Exploring the Deeper Meaning of Home" and professor emeritus of the departments of architecture and landscape architecture at the University of California, Berkeley.

For example, Dr. Israel said that while interviewing the architect Michael Graves for "Some Place Like Home," she helped him discover that he was drawn to his house in New Jersey — a former furniture repository with long, thin rooms — in part because it evoked a place of fascination from his childhood: stockyards with long, narrow pens, where his father used to work.

Buyers have varying degrees of consciousness about how their family history influences them, yet few people go to open houses pondering their childhood. Some psychologists say the deeper your awareness of your history, however, the more likely you are to buy a place that feels like home. Buyers who are less aware may end up with a place that meets all of their practical criteria and has visual razzle-dazzle, but lacks the "it just feels right" magic.

Lora Martens, who is over 40, knew she wanted her Manhattan apartment to somehow evoke her spacious childhood house in the Chicago suburbs. So when she began hunting in 2003, she looked for a place that was roomy, bright and large enough to begin a family in. Upon entering the 1,000-square-foot co-op on First Avenue and 72nd Street with her broker from Bellmarc Realty, she was sold. The living room was 30 feet long and had a 5-by-16-foot window.

"I walked in and I thought, 'That window!' " said Ms. Martens, who works for Sports Illustrated. She nabbed the place for less than $500,000 in 2004. This year, she plans to nab a boyfriend.

Jim Fraenkel, 35, an executive producer of MTV News, who is closing on his first apartment this week for about $630,000, said a 700-square-foot brownstone apartment in Gramercy "just felt right." He could envision his artwork on the walls and felt that the space, with its wood-burning fireplace and skylight, was an ideal blend of his small-town roots and his city sophistication. But while there are many things he adores about the apartment, he cannot nail down why it resonated with him. "There's a certain intangibility about it," he said.

So why do smart, articulate people find themselves at a loss for words when it comes to explaining why a place feels right? Partly because it is too amorphous and unconscious. Ms. Cooper Marcus compared it to analyzing your dreams on your own. "Expressing our feelings about environments is not something we do very much," she said.

Setha Low, a professor of environmental psychology and anthropology at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, likened the "it just feels right" experience to meeting a stranger who inexplicably feels familiar.

Some buyers even find themselves willing to give up things they wanted, like an elevator or a doorman, to live in a place that evokes that familiar feeling.

But while every buyer has different needs and desires, certain qualities — like high ceilings, natural light and views of nature — are almost universally desirable.

"When we see nature, we're going home in some genetic sense," said Robert Gifford, a professor of psychology at the University of Victoria in British Columbia and the author of "Environmental Psychology: Principles and Practice." Gazing at nature recharges our batteries, he said, referring to a theory known as "attentional restoration." Additionally, studies have shown that views of nature improve people's well-being, he said.

Another source of good feeling is a grandparent's home, often more so than a parent's, said Dr. Israel, because a grandparent's home is usually the place where the child is spoiled and the parent gets a break.

Joe, 39, who has a love of historic New York buildings, wondered whether his fondness for them stemmed from his grandparents, who collected antiques. "I'm attracted to history," said Mr. Testone, a broker. "I can't really say why."

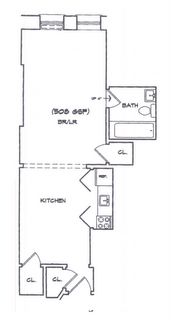

His fascination with the subject inspired him to purchase a 500-square-foot co-op in a landmark 19th-century building on Fifth Avenue and 30th Street last year for about $400,000. The old Chinese murals in the lobby, the apartment's 12-foot ceilings, crown molding and high baseboards transported him back in time, he said.As architecture and interior design buffs know, people generally look for places that represent who they are — or who they would like to be.

"The dwelling is a symbol of the self," said David Seamon, an environment-behavior researcher and professor of architecture at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kan. "In that sense the house both avows the self and reveals the self."

Jonathan Squires, 27, grew up in Boulder, Colo., and recalled that during a childhood visit to New York City, he saw an advertisement for an apartment that had hardwood floors. "I remember seeing it and thinking, 'Wouldn't it would be so cool to live in an apartment like that someday?' " he said.

Last year, someday finally came. Mr. Squires bought a 500-square-foot co-op in Morningside Heights. The floors were not the only draw, he said, but he cannot quite put his finger on why, from the moment he walked in, he knew he wanted to live there.

George Garrity, 34, had the same feeling when a Corcoran Group broker showed him a 1,200-square-foot West Village condo with unobstructed views of downtown Manhattan. He also liked the bones of the apartment and knew he could renovate it to evoke the glamour of European hotels. "I stayed in a lot of classy hotels in Europe," Mr. Garrity, a residential contractor, said. "It's reminiscent of that."

The notion of home is not merely relegated to one's private residence, however. People frequently apply the word to their neighborhood, even their country of birth. Michael D'Arminio, 40, is in contract for a co-op around $650,000 that his Bellmarc broker found for him on 29th Street, between Eighth and Ninth Avenues, because he feels it is one of the few Manhattan areas that has not become homogenized. For him, the neighborhood itself is home.

"I remember Times Square when it was prostitutes and drug addicts, when you had young people mixed with old people mixed with artists," said Mr. D'Arminio, who develops and markets perfume. "I've lived here for 20 years. I miss the edge. That was when New York was at its best."

His "it just felt right" experience began long before he was inside his apartment. Of course, there is always a chance that such a moment could be just that — a mere moment.

Dr. Gifford pointed out that spaces which instantly feel right can have impracticalities or problems. The plaster may crumble, the sink may leak and the floor may be uneven. His own home, which he immediately fell for, has ocean views. But the bathroom does not quite work, and the kitchen is in need of repair. It causes him grief from time to time. Still, he loves it.